A Personal Journey Through Japan’s Most Enigmatic Abandoned Ryokan

Introduction: A Lost Landmark Rediscovered

In 2016, I found myself standing at the edge of the Kinugawa River, camera in hand, staring up at the silent shell of Kinugawa Kan. The once-grand ryokan loomed over the valley, its empty windows staring blankly into the gorge. It was my first time exploring the site, and though the hotel had been abandoned for nearly two decades, I could still feel the echoes of its former life: the bustle of guests in yukata, the laughter drifting from banquet halls, the steam rising from the now-dry Kappa Bath. This personal connection made the exploration all the more poignant.

At the time, very little was known about Kinugawa Kan’s history. I walked its halls with more questions than answers. What stories had unfolded here? Who built this place, and why did it fall? The mystery of its past only deepened my fascination.

Nearly a decade later, the puzzle has come into focus. Through a collection of vintage postcards, brochures, city archives, and economic records, I’ve pieced together the story of Kinugawa Kan from its founding to its collapse. The thrill of discovery, combined with my own photography, this post brings together both historical context and personal exploration, offering a visual and written record of a hotel that once stood at the heart of one of Japan’s most iconic onsen towns.

Kinugawa Kan may now be a hushed ruin, but its story spans centuries, from feudal bathhouses to the exuberance of Japan’s economic bubble. This is that story.

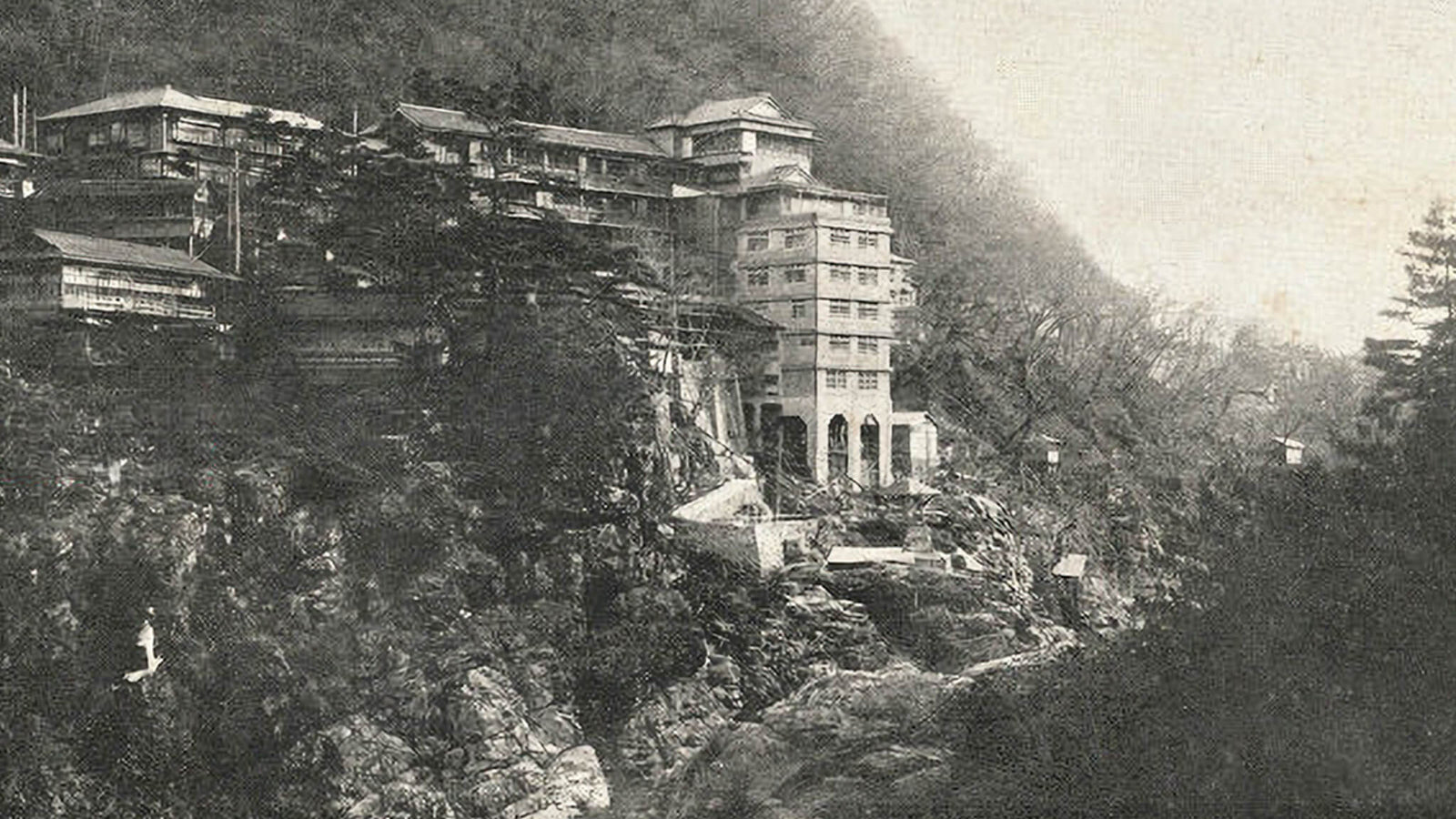

An early postcard of Kinugawa Kan, showing its dramatic position on the cliffs above the Kinugawa River. The arched base and mix of architectural styles highlight its early expansion during the prewar tourism boom.

This postcard shows Kinugawa Onsen in its early years, when small wooden ryokan lined the riverbanks. It captures a quieter era, before large-scale hotels like Kinugawa Kan transformed the landscape.

This early postcard shows a traditional riverside ryokan predating Kinugawa Kan, offering a glimpse into Kinugawa Onsen before large-scale resort development.

Kinugawa Onsen: From Sacred Waters to Spa Destination

Long before Kinugawa Kan was built, the hot springs of Kinugawa were already steeped in spiritual and historical significance. In 1691, the first recorded onsen source was discovered along the Kinugawa River, in an area then known as Taki Onsen. These natural springs were considered sacred. Reserved exclusively for Buddhist monks and samurai returning from pilgrimages to the nearby Toshogu Shrine in Nikko.

For centuries, the baths were off-limits to commoners. It wasn’t until the Meiji Restoration, in the late 19th century, that Japan’s rigid class divisions began to erode and the healing waters of Kinugawa were opened to the general public. With that shift came a new wave of travellers, merchants, artists, and city dwellers. Eager to experience the spiritual and therapeutic benefits of the onsen for themselves.

By 1927, as infrastructure improved and local inns multiplied, the area was officially renamed Kinugawa Onsen, consolidating nearby Taki and Fujiwara Onsen into a single identity. But it was the arrival of the Tobu Railway in 1929 that changed everything. With a direct line from Tokyo, Kinugawa transformed almost overnight from a remote spiritual retreat into a bustling resort town. What had once been a place for quiet reflection became a weekend getaway for the capital’s growing middle class.

Luxury ryokan began springing up along the riverbanks, catering to this new wave of leisure tourists. These inns offered tatami rooms with scenic views, multi-course kaiseki meals, and hot spring baths that framed the valley in steam and stone. Kinugawa was no longer just a place of healing. It was now a destination.

It was during this period of growth, optimism, and national transformation that Kinugawa Kan would soon make its debut.

A panoramic view of Kinugawa Onsen reveals the town’s dramatic setting, where early ryokan clings to sheer cliffs above the river below. The grand inn in the foreground, with its layered rooftops and commanding presence, reflects the architectural ambition of a growing resort town. As rail access expanded and tourism flourished, Kinugawa evolved from a secluded retreat to a thriving destination.

Gliding beneath the steel span of Kurogane Bridge, wooden boats carry kimono-clad visitors through the gorge’s still waters. Towering cliffs frame the river’s path, echoing with the quiet rhythm of early tourism in Kinugawa Onsen. Before hotels lined the valley, moments like these offered a more intimate connection to the landscape.

Two mischievous kappa dance across this Tobu Railway card, a nod to the legendary creatures said to dwell in Kinugawa’s waters. Issued for Kinugawa Kan Honten, the design celebrates the ryokan’s beloved Kappa Bath and its ties to regional folklore. More than just a prepaid card, it’s a playful relic from a time when Kinugawa Kan stood at the heart of onsen tourism.

The Birth of Kinugawa Kan: A Family Dream Turned Mega-Hotel

Kinugawa Kan (きぬ川館) was founded in 1936 by Takashi Hoshi (星堯), a local entrepreneur with a deep connection to the region’s evolving onsen culture. Unlike many early ryokan that began as modest wooden inns, Kinugawa Kan was a purpose-built establishment from the start. Hoshi envisioned a hotel that would blend traditional Japanese hospitality with the modern conveniences that a growing number of urban tourists had come to expect.

Construction began on a site perched above the Kinugawa River, where steam rising from the valley below offered both atmosphere and promise. The original structure was relatively modest by today’s standards, but it was considered ambitious at the time, a bold investment in a region still on the rise. Its architecture, interiors, and guest experience reflected both old-world charm and new-world efficiency.

From the outset, Kinugawa Kan positioned itself differently. Rather than leaning solely on traditional aesthetics, it embraced the idea of a modern ryokan: larger facilities, higher occupancy, and new technologies. This forward-thinking approach allowed it to scale rapidly in the postwar decades.

The groundwork had been laid. In the decades that followed, Kinugawa Kan would grow far beyond what Hoshi could have imagined.

Taken from a promotional brochure in the mid-20th century, this image captures Kinugawa Kan Honten perched along the cliffs of the Kinugawa River at the height of its success. With its sweeping multi-storey design and commanding views, the ryokan stood as a symbol of Kinugawa Onsen’s golden era, welcoming guests from across Japan and beyond to its famed Kappa Bath and scenic retreat.

An early photograph of Kinugawa Kan shows the ryokan in its original form, with timber construction, tiled roofs, and a grand karahafu-style entrance. Likely taken in the late Taisho or early Showa period, the scene reflects a time when Kinugawa Onsen was shifting from secluded retreat to popular travel destination. Early automobiles parked at the gate hint at the rise of modern tourism, as visitors from Tokyo arrived seeking comfort, prestige, and the healing waters of the region.

Framed by towering pines, this vintage postcard shows Kinugawa Kan rising from the valley’s wooded slopes. Captured during its peak in the 1960s or 1970s, the ryokan’s tiered form blends into the landscape, echoing the harmony between nature and hospitality that defined Kinugawa Onsen. The image reflects a time when domestic tourism flourished, and the hotel welcomed waves of visitors seeking rest beneath open skies and the sound of the river below.

Golden Years: Expansion, Luxury, and the Bubble Era Boom

By the 1960s, Japan’s rapid economic growth had transformed not just the nation’s industries, but its leisure habits as well. Domestic tourism boomed, and Kinugawa Onsen found itself at the centre of it. The increasing popularity of company retreats, family holidays, and group tours created a demand for larger, more extravagant accommodation, and Kinugawa Kan answered that call.

The hotel expanded multiple times over the next two decades. New guest wings, banquet halls, and a second annex were added in succession, eventually forming a sprawling nine-story complex of interconnected corridors, service staircases, and hidden nooks. Locals began calling it “Japan’s Kowloon Walled City,” a nickname that spoke to both its scale and its maze-like design. It became easy to get lost inside, both literally and figuratively.

Kinugawa Kan was also officially recognised as a Government-Registered International Tourist Hotel (政府登録国際観光旅館), placing it among an elite group of accommodations considered suitable for foreign visitors. This designation reflected not just size or quality, but a reputation for excellence in service and facilities.

At the centre of its allure was the Kappa Bath (かっぱ風呂), an onsen experience that tapped into both folklore and luxury. Originally constructed as an open-air bath directly in the shallows of the Kinugawa River, it was named after the mythical kappa said to inhabit Japan’s waterways. Guests would soak in steaming waters while gazing up at the cliffs above, surrounded by the murmur of the river and the playfulness of cartoon kappa featured in the hotel’s promotional materials.

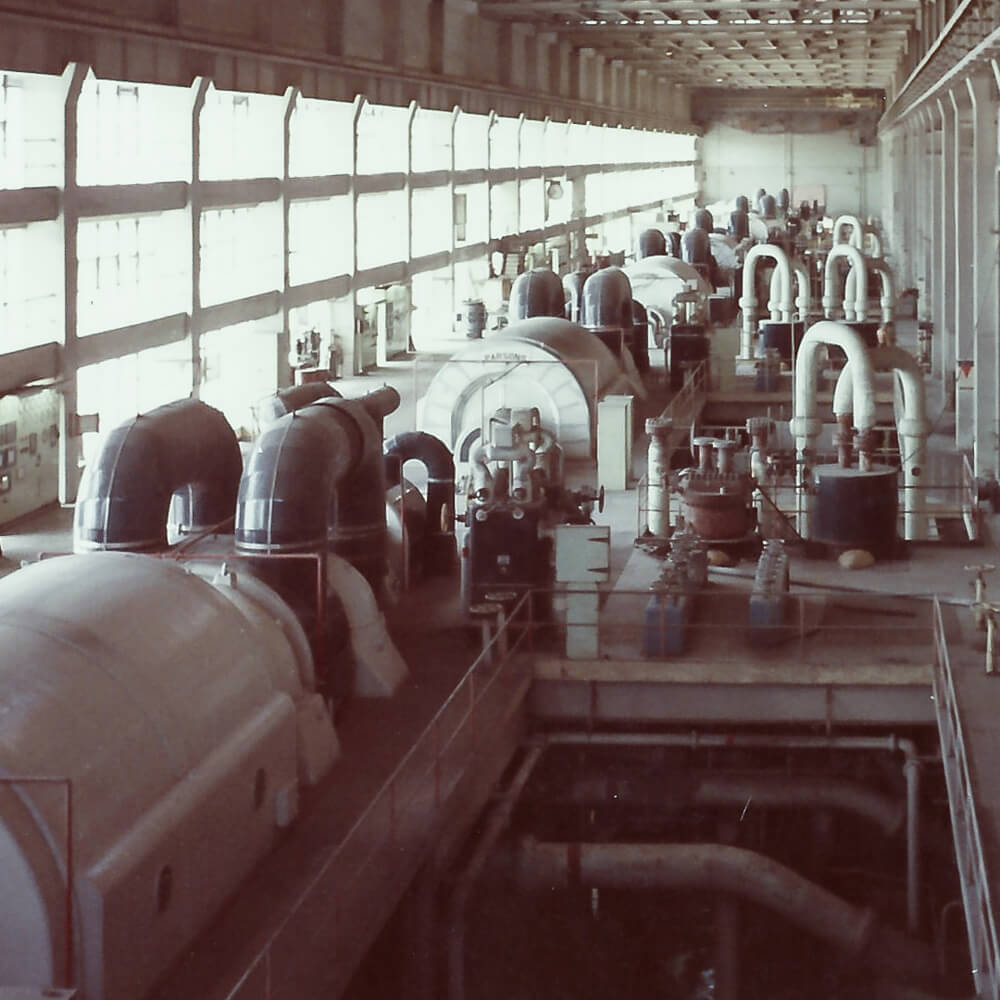

However, as Kinugawa Kan scaled up, so too did its bathing facilities. By the 1980s, the original riverside bath had been replaced with a vast indoor onsen complex. The new version of the Kappa Bath retained its name and branding, but it was now encased in tiled walls and a grand arching glass window, built for volume rather than intimacy. It was a move that reflected the times. Japan’s bubble economy rewarded scale, spectacle, and high throughput.

At its peak, Kinugawa Kan welcomed thousands of guests each year. Visitors arrived by train and tour bus, streaming into the lobby in waves, slipping off their shoes in exchange for slippers and yukata. They came for weddings, work parties, school trips, and family holidays. Some came just to see what all the fuss was about.

By the early 1990s, Kinugawa Onsen was drawing more than 3.4 million visitors annually. And Kinugawa Kan stood proudly at the heart of it all.

A 1970s promotional brochure highlights Kinugawa Kan’s transformation into a full-scale resort, complete with elegant lobbies, international stage shows, modern rooms, and onsen leisure, blending traditional hospitality with entertainment-driven appeal.

This brochure image of Kinugawa Kan Bekkan captures the ryokan’s dramatic cliffside expansion, featuring the iconic Kappa Bath and outdoor pool. It reflects a period when Kinugawa Onsen thrived as a premier resort destination.

A late 1970s brochure presents Kinugawa Kan Honten as a thriving international resort, offering signature onsen views, social spaces, and refined hospitality during the golden era of Kinugawa Onsen.

Collapse: The 1990s Crash and Bankruptcy

As the 1990s began, the mood in Japan shifted. After years of rapid expansion and unchecked optimism, the country’s economic bubble burst. Almost overnight, the financial landscape changed. Corporate travel budgets were slashed, group tours declined, and domestic leisure spending dropped dramatically. For Kinugawa Kan, which had grown aggressively during the boom years, the downturn was devastating.

The hotel had taken on substantial debt to fund its many expansions, operating on the assumption that high occupancy would continue indefinitely. However, with fewer guests and rising maintenance costs, profitability slipped out of reach. Desperate measures followed. Staff were laid off, services scaled back, and sections of the hotel closed off entirely in an effort to cut costs. Still, it wasn’t enough.

By June 1999, Kinugawa Kan declared bankruptcy with more than ¥3 billion in debt. It became the first major ryokan in Kinugawa Onsen to collapse in the post-bubble era. A shock that reverberated throughout the region. Once a symbol of success, the towering hotel now stood as a cautionary tale of overconfidence and overdevelopment.

A lounge once filled with music and conversation now lies silent, moss-covered and collapsing. Across the river, modern hotels still thrive. This one is forgotten.

Now dry and silent, the Kappa Onsen once offered warmth, reflection and views of the gorge. Only dust remains, echoing what this space used to mean.

From this decaying balcony, two worlds unfold. One alive, one abandoned. The Kinugawa River still flows, indifferent to the silence settling on this side.

The Ruin That Remains

Despite closing its doors in 1999, Kinugawa Kan was never demolished. More than two decades later, it still looms above the river. Its faded signage visible from the opposite bank, its windows slowly surrendering to the elements.

Demolition has long been discussed, but the costs are steep. Estimates place the price of tearing it down at over ¥600 million, a figure that has deterred both public and private efforts. Legal complications have added further obstacles. Ownership has changed hands multiple times, and the site’s location over an active hot spring source introduces both geological and regulatory challenges.

Perhaps most surprisingly, Kinugawa Kan retained its Government-Registered International Tourist Hotel status until 2010. More than a decade after it had been abandoned. Bureaucratic inertia, combined with the absence of clear redevelopment plans, allowed the building’s official status to linger long after its practical use had ended.

Today, Kinugawa Kan is known as one of Japan’s most iconic haikyo. A destination for urban explorers, documentary filmmakers, and photographers drawn to its decaying beauty. Though the interiors have been stripped of valuables and the structure is no longer safe to enter, its presence remains oddly magnetic. Faded tatami rooms, rusted stairwells, and crumbling banquet halls offer glimpses into a vanished era, frozen at the edge of memory.

It is no longer a hotel. It is a monument.

A rare moment of stillness remains here. The zaisu, television, and rotary phone sit untouched, a perfectly staged memory of comfort as time quietly advances beyond the walls.

This small retreat, once a place of quiet recovery, now yields to nature. A fern pushes through tatami, ceiling panels hang loose, and hospitality gives way to slow, silent collapse.

Faint light reveals stacked chairs and sagging curtains in a room that has forgotten its purpose. Mould, dust, and silence now gather where voices and celebration once lived.

Kinugawa Onsen Today: A Town in Transition

Kinugawa Kan was not the only casualty of Japan’s economic collapse. Throughout the early 2000s, several other large-scale ryokan in Kinugawa Onsen followed a similar trajectory. Rapid expansion during the bubble era, followed by financial collapse and eventual abandonment. For a time, the town’s future looked uncertain.

Yet Kinugawa Onsen did not disappear. While the skyline bears the scars of overdevelopment, the region has slowly adapted to changing tourism trends. Many smaller, family-run ryokan weathered the storm, pivoting toward niche experiences, personalised service, and modern renovations. Others, like the historic Asaya Hotel, founded in 1888, reinvented themselves entirely, blending luxury with tradition in a way that appeals to both domestic and international visitors.

Efforts to redevelop the abandoned properties have been slow and complex. In collaboration with Utsunomiya University, Nikko City has explored a range of proposals, from eco-tourism projects to cultural heritage centres. But turning ideas into action has proven difficult. The high cost of demolition, unclear ownership of many sites, and limited funding have stalled even the most promising plans.

Some have suggested that haikyo tourism itself might hold the key, a way to respectfully incorporate select ruins into a managed, educational experience that explores Japan’s post-bubble history. Others argue that safety and liability concerns make that vision unrealistic.

For now, Kinugawa Onsen continues to straddle two worlds: one rooted in its past as a high-traffic resort town, and another still searching for a sustainable future. Between them stands Kinugawa Kan, unchanged but never ignored. A lingering reminder of what was, and what might still be.

The glow of forgotten screens lingers in a space once filled with laughter. Now, the silence is broken only by mould creeping across the walls and rain slipping through broken ceilings.

Once a refined dining area, now a shrine to disorder. The colourful mosaic and scattered teapots remain, but moss creeps in and memories fade, tangled with myth and decay.

Dim light filters into a room of collapse. A toppled rice cooker, rusted pipes and fallen beams speak to the slow dismantling of a place that once powered comfort behind the scenes.

Reflections from the Photographer: Revisiting Kinugawa Kan

Returning to Kinugawa Kan through research has been as immersive as standing in its ruined halls. In 2016, all I had were unanswered questions and a camera. Now, with access to vintage postcards, old brochures, city planning reports, and economic records, the fragments of this hotel’s story have formed something whole, or at least, something close to it.

There’s a strange familiarity in comparing the historic materials to my own images. The river still cuts through the valley with the same force. The ridgelines are unchanged. In the old postcards, you can see guests in yukata gazing out over the gorge. The same view I stood before, though under very different circumstances. What once welcomed laughter, clinking glasses, and lantern light now holds only silence.

Kinugawa Kan is not just an abandoned hotel. It is a time capsule, a physical trace of Japan’s ambitions, miscalculations, and transitions. The building may be empty, but it continues to speak. Not just about economic boom and bust, but about how spaces age, how places endure, and how memory persists in architecture.

This project is not about nostalgia. It is about preservation, understanding, and seeing beyond the decay. Through photography, I have tried to capture both the atmosphere and the evidence. Not just the way the site looks, but what it once meant.

Overgrown and silent, Kinugawa Kan rises above the valley as a fading monument to a grander era. Its balconies now overlook the forest, vines creeping through the ruins of hospitality.

The Kinugawa River surges past a forgotten stone bath, its waters untouched by time. Around it, relics of tourism and traces of nature continue their quiet tug-of-war across the gorge.

A quiet moment of reflection inside the Kappa Bath, captured in the mirror during my 2016 visit. Sometimes the camera reveals not just the subject, but the person still searching for the story behind it.

See the Full Kinugawa Kan Print Collection

This project began with a single visit and a sense of curiosity. What it became is something far larger, a visual and historical record of one of Japan’s most iconic abandoned hotels. Every corridor, every window, every image tells part of the story.

If this history has resonated with you, I invite you to explore the full collection of prints. These photographs, paired with archival materials, offer a glimpse into both the grandeur and the stillness that define Kinugawa Kan.

Leave a comment (all fields required)